2.10.1 Gaussian Quadrature

Measurable Outcome 2.14, Measurable Outcome 2.17, Measurable Outcome 2.18

The finite element method requires the calculation of integrals over individual elements, for example,

While in some settings these integrals can be calculated analytically, often they are too difficult. In this situation, numerical integration methods are used.

Gaussian quadrature is one of the most commonly applied numerical integration methods. Gaussian quadrature approximates an integral as the weighted sum of the values of its integrand. Consider integrating the general function \(g(\xi )\), over the domain \(-1 \leq \xi \leq 1\). Gaussian quadrature approximates this integral as a weighted sum of the values of \(g\) evaluated at discrete points over the domain:

Here we have used \(N_ q\) quadrature points (i.e., integrand evaluations). \(\xi _ q\) is the location of the \(q\)th quadrature point in the domain and \(\alpha _ q\) is the corresponding quadrature weight.

Note that Gaussian quadrature rules are developed for specific integration limits, in this case between \(\xi = -1\) to \(+1\). Thus, for integration in an element, we will need to transform from \(x\) to \(\xi\).

Gaussian quadrature integration rules are determined by requiring exact integration of polynomial integrands, i.e., by considering integration of the function

for all values of the \(c_ m\) coefficients. Note that

This gives us the result:

The \(N_ q = 1\) Quadrature Rule

For \(N_ q=1\), the quadrature rule is

Now, using Equation (2.225), we determine the highest order polynomial that is integrable by a single quadrature point:

Matching term by term gives

Then, checking the \(c_2\) term shows that it is not integrated exactly. So, with one point, a linear polynomial is the highest order polynomial that can be evaluated exactly and the quadrature rule is

The \(N_ q = 2\) Quadrature Rule

For \(N_ q=2\), the quadrature rule is,

Again using Equation (2.225), we determine the highest order polynomial that is integrable by two quadrature points:

Matching the first four terms gives the following constraints:

These constraints can be met by choosing

Thus, this rule will integrate cubic polynomials exactly.

Calculation of Forcing Integral with Gauss Quadrature

We wish to apply Gaussian quadrature to evaluate the forcing integral,

Remember that this is the last term in the definition of the weighted residual for our diffusion problem, Equation (2.211).

To do this, we first transform between the \(x\) and \(\xi\) space. For this integral in element \(i\), the transformation is

Substitution in the forcing integral gives

Note that the dependence of \(\phi _ i\) and \(f\) on \(\xi\) is shown through the dependence of these functions on \(x = x(\xi )\). However, for the basis functions, it is often easier to directly determine \(\phi _ i\) from \(\xi\). For example, in the case of linear polynomial basis functions, the basis functions with element \(i\) can be written as

Clearly, these functions vary linearly with \(\xi\). \(\phi _1(\xi )\) is one at \(\xi =-1\) and decreases linearly to zero at \(\xi =+1\). \(\phi _2(\xi )\) is zero at \(\xi =-1\) and increases linearly to one at \(\xi =+1\).

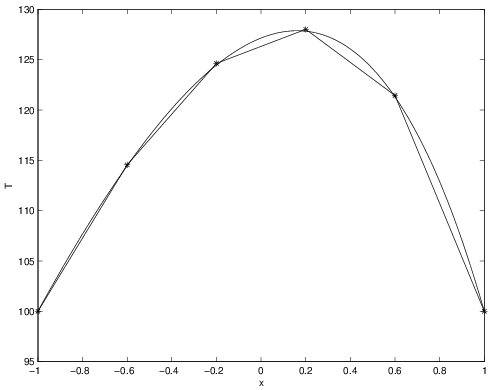

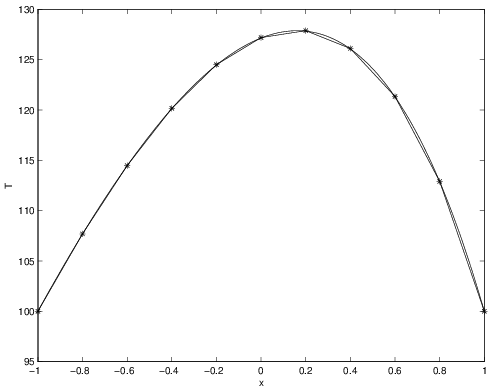

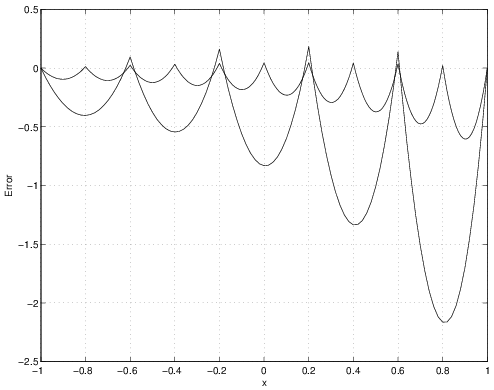

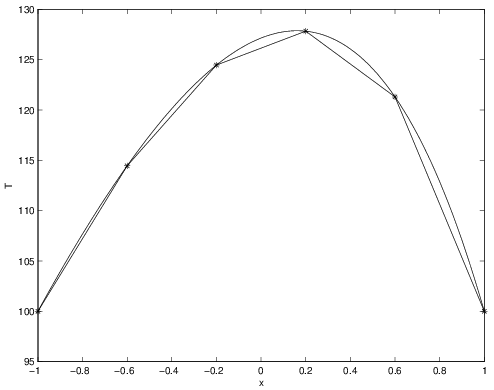

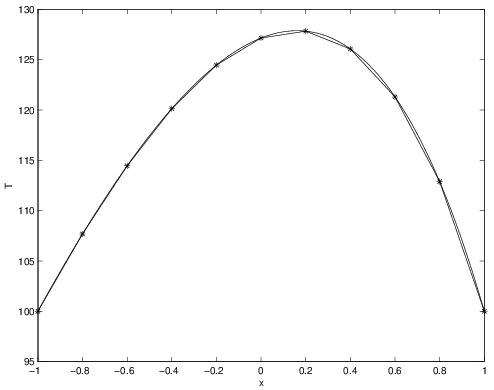

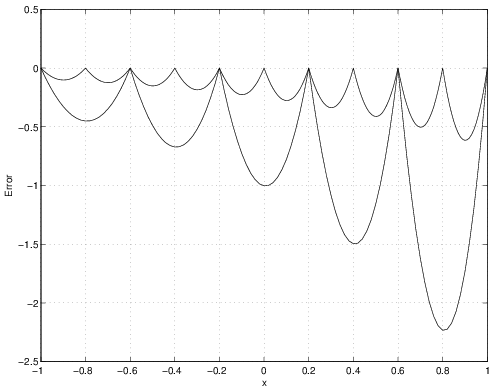

The following is a MATLAB® script that uses Gaussian quadrature to evaluate the forcing integral and solve the problem described in Section 2.8.1. The number of points being used is set at the beginning of the script. Results for both 1-point and 2-point quadrature are shown in Figures 2.41-2.46 for \(5\) and \(10\) elements. While the 2-point quadrature rule has lower error than the 1-point rule, both appear to be second-order accurate since the errors reduce by nearly a factor of \(4\) for the factor 2 change in mesh size. Also, the results are no longer exact at the nodes like they were in Section 2.9.3 (though the 2-point quadrature rules are quite close).

% FEM solver for d2T/dx2 + f = 0 where f = 50 exp(x)

%

% BC's: T(-1) = 100 and T(1) = 100.

%

% Gaussian quadrature is used in evaluating the forcing integral.

%

% Note: the finite element degrees of freedom are

% stored in the vector T.

% Number of elements

nElem = 5;

x = linspace(-1,1,nElem+1);

% Set quadrature rule

Nq = 2;

if (Nq == 1),

alphaq(1) = 2.0; xiq(1) = 0.0;

elseif (Nq == 2),

alphaq(1) = 1.0; xiq(1) = -1/sqrt(3);

alphaq(2) = 1.0; xiq(2) = 1/sqrt(3);

else

fprintf('Error: Unknown quadrature rule (Nq = %i)\n',Nq);

return;

end

% Zero stiffness matrix

K = zeros(nElem+1, nElem+1);

F = zeros(nElem+1, 1);

% Loop over all elements and calculate stiffness and residuals

for elem = 1:nElem,

n1 = elem;

n2 = elem+1;

x1 = x(n1);

x2 = x(n2);

dx = x2 - x1;

% Add contribution to n1 weighted residual due to n1 function

K(n1, n1) = K(n1, n1) - (1/dx);

% Add contribution to n1 weighted residual due to n2 function

K(n1, n2) = K(n1, n2) + (1/dx);

% Add contribution to n2 weighted residual due to n1 function

K(n2, n1) = K(n2, n1) + (1/dx);

% Add contribution to n2 weighted residual due to n2 function

K(n2, n2) = K(n2, n2) - (1/dx);

% Evaluate forcing term using quadrature

for nn = 1:Nq,

% Get xi location of quadrature point

xi = xiq(nn);

% Calculate x location of quadrature point

xq = x1 + 0.5*(1+xi)*dx;

% Calculate f

f = 50*exp(xq);

% Calculate phi1 and phi2

phi1 = 0.5*(1-xi);

phi2 = 0.5*(1+xi);

% Add forcing term to n1 weighted residual

F(n1) = F(n1) - alphaq(nn)*0.5*phi1*f*dx;

% Add forcing term to n2 weighted residual

F(n2) = F(n2) - alphaq(nn)*0.5*phi2*f*dx;

end

end

% Set Dirichlet conditions at x=-1

n1 = 1;

K(n1,:) = zeros(size(1,nElem+1));

K(n1, n1) = 1.0;

F(n1) = 100.0;

% Set Dirichlet conditions at x=1

n1 = nElem+1;

K(n1,:) = zeros(size(1,nElem+1));

K(n1, n1) = 1.0;

F(n1) = 100.0;

% Solve for solution

T = K\F;

% Plot solution

figure(1);

plot(x,T,'*-');

xlabel('x');

ylabel('T');

% For the exact solution, we need to use finer spacing to plot

% it correctly. If we only plot it at the nodes of the FEM mesh,

% the exact solution would also look linear between the nodes. To

% make sure there is always enough resolution relative to the FEM

% nodes, the size of the vector for plotting the exact solution is

% set to be 20 times the number of FEM nodes.

Npt = 20*nElem+1;

xe = linspace(-1,1,Npt);

Te = -50*exp(xe) + 50*xe*sinh(1) + 100 + 50*cosh(1);

hold on; plot(xe,Te); hold off;

% Plot the error. To do this, calculate the error on the same

% set of points in which the exact solution was plot. This

% requires that the location of the point xx(i) be found in the

% FEM mesh to construct the true solution at this point by linearly

% interpolating between the two nodes of the FEM mesh.

Terr(1) = T(1) - Te(1);

h = x(2)-x(1);

for i = 2:Npt-1,

xxi = xe(i);

Tei = Te(i);

j = floor((xxi-xe(1))/h) + 1;

x0 = x(j);

x1 = x(j+1);

T0 = T(j);

T1 = T(j+1);

xi = 2*(xxi - x0)/(x1-x0)-1; % This gives xi between +/-1

Ti = 0.5*(1-xi)*T0 + 0.5*(1+xi)*T1;

Terr(i) = Ti - Tei;

end

Terr(Npt) = T(nElem+1) - Te(Npt);

figure(2);

plot(xe,Terr);

xlabel('x');

ylabel('Error');