In this section, Wit Busza distinguishes between the physics and the mathematics involved in physics problems. He discusses how this distinction helps him determine if students have understood the essence of a problem.

Physics problems have two fundamentally different parts—and the two parts reflect the core of the scientific method. The first part relates to what I call “physical laws in action” (or understanding the physics). It requires that students have the ability to translate physical situations into mathematical expressions. The second part involves actually doing the mathematics. When students have trouble solving a problem, it’s very important that the teacher identify which of the two parts is causing the student difficulty. In my experience, teachers rarely do this.

Part I: Translating Physical Situations into Mathematical Equations

Physics problems have two fundamentally different parts—and the two parts reflect the core of the scientific method.

—Wit Busza

I can recall infinite examples of students coming to me and saying, “I don’t get it. I really understand the physics, but I can never seem to solve the problems. What’s wrong?” The answer to that, nearly always, is, "You don't understand the physics." Although most students think setting up the problem is trivial, it is actually the hardest part of solving a problem. I often ask students to first visualize the mechanical parts, to see how they are interconnected, and to draw a diagram of what's going on in the problem. You’d be amazed how often they get that wrong! So many students have difficulty visualizing in two- and three-dimensions.

When I remember my own experience in primary school, we often had word problems. You know, somebody came in with two apples and did this and that to them, etc. I sometimes had difficulty actually keeping track of what was going on. See, that's not mathematics. That is the ability to convert language into a picture of what's going on. And that's a big problem for students. But that's not the end.

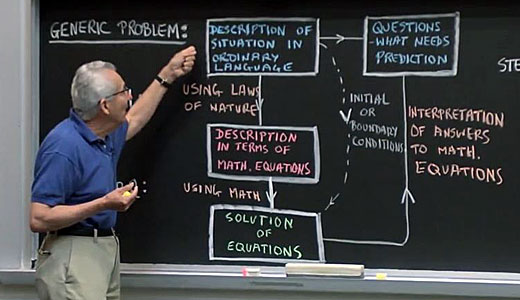

Now, you have to take that description of the situation in ordinary language—say, for example I'm holding a ball in my hand three meters above the floor and then I let go—and translate it into mathematics.

So this ball starts falling. How does it fall? And at this stage, you can visualize it, maybe, but you need the laws of nature to translate that into mathematical form. That ball goes faster and faster, which mathematically means that the second derivative of its position is not 0, but it is some constant—g in this case. So once you visualize the picture, even if you can imagine what goes on, you still now have to translate that into mathematics. And that's the physics—understanding nature, how the system behaves. All of this is the first part of doing the problem, and, I repeat, this is the hardest part. But most students think this is the easy part and the rest is hard!

Flow diagram for solving physics problems (from the Problem Solving Help Video, “Simple Harmonic Motion and Introduction to Problem Solving”).

It’s possible to help yourself in different ways. For example, if it's a mechanics problem, you draw a force diagram. It’s amazing how much knowledge and experience you have to have just to draw the so-called force diagram. You have to realize that quantities like velocity, acceleration, force, etc., can be represented mathematically in terms of vectors. You have to identify all relevant parts of the problem and then represent them in terms of mathematical quantities.

So, in a typical problem, the physical situation gets reduced to an equation, plus things we call "boundary conditions" or "initial conditions.” I have a ball. I'm holding it in my hand. And what happens to it depends on when I let go of it. Will I let go of it now or in an hour's time? It will do the same motion, but the mathematical description of it will be slightly different in the two cases. So the first stage in a problem consists of translating the physical situation, plus all initial and boundary conditions, into mathematical expressions.

Part II: Solving the Mathematical Equations

The mathematical description of the problem marks the end of the first stage. Next, we do something miraculous: We forget that the mathematical equations and boundary conditions have anything to do with physics. We put these equations into a computer, or we ask our friendly mathematics professor to solve the equations. We don't have to tell the computer this has anything to do with a physical problem. To the professor, we only need to say, “Look, I have these equations with these boundary conditions. What will happen to the value with time of this quantity as a function of that quantity?” Stage two has nothing to do with physics! We’ve entered the world of mathematics. Only after you have solved the equations—and, of course, you must do that correctly—can you return to physics. This involves knowing the rules for identifying what actually happens from the solution to your equations.

Weighting Physics More than Mathematics in Grading

I try to give more than 50% of a student's grade for the physics involved in a problem.

Students hate this, because they'll come and say, “Look, in the first two lines I made a few stupid errors. And then I did three pages of mathematics, which I got right. And you've given me only 40% of the grade. That's not fair.” Sure, the student may have got all the mathematics right, but she or he missed the essence of the problem. I think it’s very important that the grading clearly convey a message about what is important.

This resistance to weighting the physics more than the mathematics in grading assignments is the reason students hate multiple-choice problems and why the moment you give multiple-choice problems, the grades drop dramatically. In a multiple-choice problem, you have to understand the essence of the problem. You cannot just guess. And so you either understand which of the five laws of nature are applicable or you don't. There is no partial credit. Students who are not particularly strong in the subject are notorious for surviving on partial credit. If they have a good memory, they can pass a course in physics without understanding any physics at all because they can earn partial credit for the mathematics and their memory. With multiple-choice questions, memory doesn't help so much. Of course, I am assuming that the choices are well thought-out.