Course and Learning Objectives

Physical and Computational Infrastructure

Course Meeting Times

Lectures: 2 sessions / week, 1.5 hours / session

Recitations: 1 session / week, 1 hour / session

Prerequisites

18.085 Computational Science and Engineering I

Course Description

This course covers the following topics:

- Engineering systems modeling for design and optimization.

- Selection of design variables, objective functions and constraints.

- Overview of principles, methods and tools in multidisciplinary design optimization (MDO) for systems.

- Subsystem identification, development and interface design.

- Review of linear and non-linear constrained optimization formulations.

- Scalar versus vector optimization problems from systems engineering and architecting of complex systems.

- Heuristic search methods: Tabu search, simulated annealing, genetic algorithms.

- Sensitivity, tradeoff analysis, goal programming and isoperformance.

- Multiobjective optimization and Pareto optimality.

- System design for value.

- Specific applications from aerospace, mechanical, civil engineering and system architecture.

Purpose and Target Audience

This course is offered for graduate students who are interested in the multidisciplinary design aspects of complex systems. These aspects appear frequently during the conceptual and preliminary design phases of complex new systems and products, where technical disciplines (structures, propulsion, aerodynamics, controls, optics etc…) and non-technical disciplines (lifecycle costing, manufacturing, environmental impact analysis, marketing, etc…) have to be tightly coupled in order to arrive at a competitive solution. During the product development process (PDP) both quantitative and qualitative effort streams are present, where qualitative work gives rise to quantitative questions and vice-versa. This course is mainly focused on the quantitative aspects of design and presents a unifying framework called "Multidisciplinary System Design Optimization" (MSDO). We will always attempt to show the strengths of MSDO, but also its limitations in the greater qualitative context of design. A simple way to say this is: "Conceptual design and system architecting define the design vector, quantitative, computational design attempts to populate this vector with values that will lead to a good product or system". The objective of the course is to present tools and methodologies for performing system optimization in a multidisciplinary design context. Focus will be equally strong on all three aspects of the problem: (i) the multidisciplinary character of engineering systems, (ii) design of these complex systems, and (iii) tools for optimization. A more detailed discussion of these three aspects along with working definitions can be found in Appendix A. The course content is applicable to the design of a broad range of systems including space systems, aircraft, automobiles, marine and transportation systems as well as the energy, civil architecture and telecommunications sectors, among others. This subject is designed to be fundamentally different from a traditional university optimization course.

Given the multidisciplinary nature of the course, we expect significant interest from IDSS students, graduate students from the various School of Engineering departments, students enrolled in the Computation for Design and Optimization (CDO) program and potentially students from the Sloan School of Management. The course is targeted for second year graduate and Ph.D. level students.

Need Assessment

This course, we believe, is an essential component of MIT offerings in system optimization. There currently is a strong and comprehensive program in optimization methods, mainly via Course 15 (Sloan), the Computation for Design and Optimization (CDO) program and the Operations Research Center (ORC). Many OR courses focus on optimizing the efficiency of operations of systems (e.g. airline schedules, inventory levels in supply chains …) rather than on optimizing their designs from an engineering perspective. Many traditional OR problems can be formulated as linear programs (LP) or mixed-integer programs (MIP) with potentially linear objectives and constraints and a convex decision space. This course, 16.888/IDS.338J, however focuses on applying optimization techniques in a multidisciplinary design context. We will cover topics such as system characterization for multidisciplinary analysis and optimization, trade-off analysis, heuristic techniques and multiobjective optimization for the design of complex, multidisciplinary systems such as aircraft, spacecraft, automobiles, buildings, transportation systems and communication networks.

The current catalog of optimization courses at MIT focuses heavily on two areas: The first is linear programming (simplex, interior point methods, large scale optimization) which are widely applicable and can solve many problems in management, revenue optimization, production planning and scheduling. The second area is related to systems, which can be described by a set of continuous partial differential equations (PDE). Here convex, constrained optimization methods such as steepest gradient search, projected gradient and Newton's method are important and must be covered well. This course fills the gap in the areas of multidisciplinary design, heuristic methods and multiobjective optimization.

Course and Learning Objectives

The course

- supports MIT's offerings in the area of analysis and optimization of multidisciplinary systems during the "conceive" and "design" phases

- develops and codifies a prescriptive approach to multidisciplinary modeling and quantitative assessment of new or existing system/product architectures

- engages faculty and graduate students in the emerging research field of MDO, while providing an opportunity to anchor the CDIO (conceive-design-implement-operate) principles in the graduate curriculum

The students will

- learn how MSDO can support the product development process of complex,

- multidisciplinary engineered systems

- learn how to rationalize and quantify a system architecture or product design problem by selecting appropriate objective functions, design parameters and constraints

- subdivide a complex system into smaller disciplinary models, manage their interfaces and reintegrate them into an overall system model

- be able to use gradient-based numerical optimization algorithms, e.g. sequential quadratic programming (SQP) and various modern heuristic optimization techniques such as simulated annealing (SA) or genetic algorithms (GA) and select the ones most suitable to the problem at hand

- perform a critical evaluation and interpretation of analysis and optimization results, including sensitivity analysis and exploration of performance, cost and risk tradeoffs

- be familiar with the basic concepts of multiobjective optimization, including the conditions for optimality and Pareto front computation techniques understand the concept of design for value and be familiar with ways to quantitatively assess the expected lifecycle cost of a new system or product

- sharpen their presentation skills, acquire critical reasoning with respect to the validity and fidelity of their MSDO models and experience the advantages and challenges of teamwork

Pedagogy

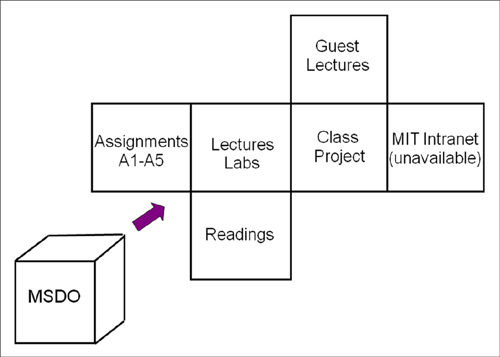

Our goal is that students will acquire knowledge and skills in the principles, methods (techniques) and tools of multidisciplinary, computational design. To this end the course pedagogy will be using a number of activities to achieve the learning objectives. Figure 1 shows the different pedagogical instruments used in the MSDO course as the sides of an imaginary folded box. In order to understand the box, one needs to look at it from all sides.

Figure 1: Pedagogy of MSDO along with some specific examples.

Lectures: The lectures are 90 minutes long and take place twice a week. We lecture mainly using PowerPoint slides, but enhance the material with some active learning exercises and handouts. The lectures are broken down into four modules:

Module 1: Problem Formulation and Setup L1-L5

Module 2: Optimization and Search Methods L6-L13

Module 3: Multiobjective Optimization and Visualization L14-L18

Module 4: Implementation Issues and Applications L19-L24

Labs: Bi-weekly laboratory sessions/recitations will be conducted by the TA to help solve the homework assignments A1-A5 and to get students familiar with computational tools and approaches. Attendance at the lab sessions is not mandatory but recommended.

Guest Lectures: Will provide an outside perspective and show industrial applications

Readings: Will use the recommended textbook and give an overview of the published literature in the field. Normally readings are assigned at the end of each lecture in preparation of the next lecture.

Assignments: (Part a) Will challenge the students and ensure that all participants apply and deepen the theoretical knowledge from the lectures, regardless of their disciplinary background. Some of the assignments will involve computation. (Part b) The second part of the assignments provides an opportunity to gradually develop the term project throughout the semester. This provides a coupling with the student's research interests.

Term Project: This is central to the success of the course. Students form small teams with between two and three members (no individual projects!). They can choose between a number of sample projects provided by the faculty or pick a project based on their own research. The semester culminates with a final project presentation and writing a final report in the form of a conference article. Each group will select a multidisciplinary system to study throughout the semester. Examples include (but are not restricted to) an aircraft, a space system, an automobile, a communications network or a transportation system. The faculty will screen the project proposals during the first two weeks and offer advice in problem selection and scoping if necessary. The projects will parallel the lecture content. The overall aim is to teach general tools and methods in the lectures, while allowing students to apply these tools to a specific application that is aligned with their background and interests.

Detailed Syllabus

Module 1: Problem Formulation and Setup

- System characterization:

- Identification of objectives, design variables, constraints, subsystems

- System-level coupling and interactions

- Examples of MSDO in practice

- Visualization techniques in design optimization

- Subsystem model development:

- Model partitioning and decomposition, interface control

- Collaborative Optimization, Bi-Level Formulations

- Subsystem model selection: fidelity versus expense

- Model and simulation development and validation

Module 2: Optimization and Search Methods

- Optimization and exploration techniques:

- Review of linear and nonlinear programming

- Heuristic techniques: genetic algorithms simulated annealing, Tabu search

- Design Space Exploration: Design of Experiments (DOE): Full factorial search, parameter study, Taguchi/orthogonal arrays, latin hypercubes

- Mixed integer programming (application to hub spoke / network problems)

- Sensitivity and post-optimality analysis:

- Jacobian matrix, Hessian, finite differences

- Adjoint methods and Lagrange multipliers

Module 3: Multiobjective and Stochastic Challenges

- Multiobjective optimization:

- Weighted sum optimization

- Weak and strong dominance

- Pareto front computation

- Goal programming and isoperformance

- Physical Programming

- Multiattribute Utility Theory

- Introduction to robust design

- Monte-Carlo Sampling

- Design under uncertainty

- Reliability analysis, Taguchi methods

Module 4: Implementation Issues and Real World Applications

- System assessment and extensions:

- What is optimality?

- Design for value: including lifecycle costing

- Optimizing product families and platforms

- Implementation issues:

- Model reduction

- Approximation techniques: response surfaces, kriging, neural networks

- Concurrent design

Physical and Computational Infrastructure

For their projects and homework assignments, the students will be free to choose the platform and software of their choice. They can code their simulation modules in MATLAB®, Excel (Visual Basic®), Java™, FORTRAN or C/C++, among others. In terms of using optimization software, we recommend the following alternatives:

iSIGHT®: This is currently one of the most popular multidisciplinary design optimization software available on the market. This tool is state-of-the-art and is used in many large corporations that focus on the design and development of large, complex engineering systems.The program can be "wrapped around" any user specific simulation code (e.g. in Excel, MATLAB, C, FORTRAN…) and has excellent design space exploration, optimization and robust design capabilities. The developer of iSIGHT is Engineous Software, Inc., located in North Carolina. The company has since been purchased by SIMULIA, a part of Dassault Systems. The origin of this tool is the "Software Robot" developed by Dr. Siu Tong during his doctoral research at MIT, Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, from 1979-1983.

PHX ModelCenter 3: This is a visual environment for process integration to support your design projects. With PHX ModelCenter, you can quickly create an engineering process and then perform complex design exploration techniques to find the best design. PHX ModelCenter is adaptable, and works well with groups whose design processes change frequently. PHX ModelCenter automates the process of running the hundreds of design programs you use during a typical design project. Using PHX ModelCenter design data is automatically passed from one program to another, freeing you to concentrate on the results of the design and not the drudgery of running individual programs.

Other options include: MATLAB Optimization Toolbox, and Excel Solver. It is the responsibility of the students to create for themselves the computational infrastructure that suits them best.

The use of commercial disciplinary codes such as MSC/NASTRAN for structural modeling, Pro/ENGINEER®, SolidWorks® for Computer Aided Design or IBM CPLEX for the solution of linear programs is also a possibility for your projects. There will be less emphasis on this point, however, since proficiency in these tools takes a long time to acquire and many of these codes have steep learning curves. Hence, the emphasis of the course is rather on learning the process of setting up, solving and interpreting multidisciplinary problems, rather than on creating physical models of very high fidelity as would be expected in an industry environment.

Grading

There will be two types of assignments in the course:

Assignments 1-5 (5 Total)

Part (a): Small, simple problems to be solved individually, many just by hand or with a calculator. Goal is to ensure learning of the key ideas regardless of chosen project. Some problems might require more extensive computation.

Part (b): Application of theory to a project of your choice from either existing class projects or a project related to your research. We expect team sizes between two and four students.

The assignments are due bi-weekly. Typically an assignment is handed out on a WednIDSay, and is due on a Monday two weeks later. There will be informal labs/recitations in order to help students work through issues associated with the assignments.

Class Project

The class project is our main means of assessing whether you can learn the material at a deeper level and apply it to a graduate level research project. There are two major deliverables here towards the end of the term:

- Project Presentation (ca. 15-20 minutes including Q&A)

- Final Report in the format of a journal or conference article

| ACTIVITIES | PERCENTAGES |

|---|---|

| Assignments 1-5 (10% each) | 50% |

| Project presentation | 20% |

| Final project report | 20% |

| Active participation/attendance | 10% |

Appendix A

This appendix discusses the aspects of the MSDO course:

Multidisciplinary

A key component of this course is learning how to integrate different models from various disciplinary fields together into a single macro-model. All too often specialists in different fields (structures, fluids, propulsion, controls etc.) exert a great deal of effort modeling and designing within their area of expertise with little understanding of how their design decisions affect other subsystems within the entire system. Also frequently lacking is an understanding of how such design decisions impact system lifecycle cost and program risk. Understanding of and fluency in integrated, multidisciplinary modeling is essential to the success of contemporary and future complex systems.

System

A system is a physical or virtual object that is composed of more than one element and that exhibits some behavior or performs some function as a consequence of interactions between these constituent elements.

Design

This course focuses on engineering design problems (e.g. aerospace vehicles, transportation systems, communication networks) and not primarily management problems (resource allocation, supply chain optimization, revenue management, etc.). As such, students should have a background and interest in engineering and system or product design and have had previous exposure to optimization. The course will be a good complement to existing courses in product development and system architecture, which do not typically present a multitude of quantitative methods and tools.

Optimization

Optimization is a mathematical method and gives rise to a number of algorithmic tools. As such it represents a bridge, which enables the use of integrated multidisciplinary models to do more effective design engineering work. It should be stressed that the use of optimization is not intended to remove the human from the design loop. Rather, optimization enables engineers and system architects to explore vast design spaces, often resulting in non-intuitive insights. This may result in system designs that are more cost-effective compared to previously considered traditional designs.