« Previous

Session Overview

|

How do we think? What does it mean to be intelligent or creative? This discussion session complements the prior lecture sessions Thinking and Intelligence. |

Demonstration

Do We Think in Words or Pictures?

Listen as Tyler poses one of the big questions in early psychology: do we think in words or pictures? (MP3) (0:02:40)

Transcript: "Thinking...mentally manipulating information. Who said that earlier? That's exactly right.

There was an argument for a long time about whether we thought using words or using pictures. And this is one of those things, like, why did psychologists argue about this? Who thinks that this is...anyway? For a long time, early psychologists thought that thinking was just sub vocal speaking, that you were just talking to yourself in your head, and that was what constituted thinking about something.

What do you guys think about that? Do you think that thought is really just talking to yourself in your head? Is that all you do when you're thinking, just talk to yourself in your head? I mean, you do. "Okay, guys, what do we have to do today?" You probably don't call yourself "guys," but, "Okay, Tyler, what do I have to do today? I have to give a lecture, then I have to go get lunch, mmm, it's Chang burger day at Whitehead. Then I gotta come back; I have a meeting with John at 2, so I gotta put my data together. Then after the meeting, I'm just gonna be depressed, so I'm gonna have to do something fun for the rest of the day."

You think to yourself in words, right, but are you always thinking to yourself in words? No. It feels like we see the world in our head, right? What are some examples of when you think in pictures, for example?

There's some interesting psychological evidence to show that we really do think in pictures, that it matters that we think in pictures for how we relate to the world. There are two good examples of this, and I'm surprised Dr. Gabrieli didn't talk about it in class. I wonder if we'll get to it later in the semester. They're really exciting examples, and they're in the book.

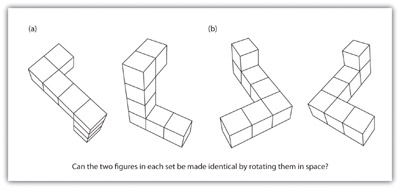

Mental rotation: So, when you're shown an abstract 3D shape and another abstract 3D shape, and you say, "Are these exactly the same?" But they're in different positions, and your job is to decide if they are exactly the same. How would you do this, if you had to think about it?

Figure 1. 3D Shapes for Spatial Rotation Task Test. (Courtesy of Flat World Knowledge. Source: [Stangor])

Would you measure it out in your mind, like, "Alright, we've got a right angle here, a right angle there, and these things project orthogonally? There's this whatever at the end."

Would you think about it in words? How would you decide if these two shapes are exactly the same? Like Tetris pieces...mentally rotate them! "I got these two shapes, I want to see if they're the same...mmm...check!" You do that in your head.

How could we prove, using science, that you're really doing that in your head? We could ask you, but we're not always the best judge of ourselves."

Experimental Evidence for Thinking in Pictures

Listen next as Tyler describes how experiments have shown that people are truly thinking in pictures: (MP3) (0:01:27)

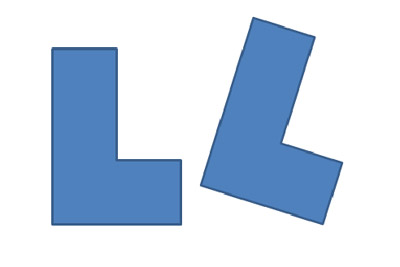

Transcript: "Let's think about it for a second. If I give you two L-shapes, like this and like this, so they're just a little bit off, and you rotate them to show me that they're the same. On paper, if I give you these two things, these two objects in front of you, how long is it going to take you to show that these two are the same?

Figure 2a. L-shape patterns with similar rotation.

Two seconds, right, because you go "er" and they're the same. You're amazing.

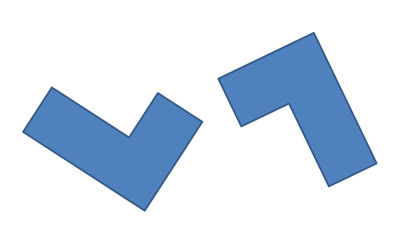

What if I give you two L-shapes like this? How long is it going to take you to rotate them and prove that they're the same?

Figure 2b. L-shape patterns with more rotation.

A little longer, because you've got to go "brrrrr, check, alright, they're the same."

So now I'm going to ask you to imagine, are these two exactly the same, the two L-shapes? Yes, because if you go "check!", now I want you to imagine if they are exactly the same. Is it going to take you longer to imagine that these two (Figure 2a) are the same, than that these two (Figure 2b) are the same?

In fact, it does. It's a linear relationship between how much you've rotated it, in terms of angle of rotation, and how long it takes you to say that two shapes are the same, if you're just imagining it in your head. The same way as if you have to rotate them on paper.

It takes you longer as you make them farther apart in rotation. Isn't that pretty good evidence that we're actually doing the mental rotation in our mind? Pretty good evidence, right? Exactly the same as if we had to rotate the shapes in reality, it takes us longer in our mind to say that they're the same. It's kind of evidence against the verbal description too, because we can form the verbal description in the same amount of time, whether it's like this or like that."

Think About

The idea of creativity is that people can come up with very novel solutions, or very novel interpretations that others haven't seen before. Great artists are doing this all the time – they see the world in a way that nobody else sees. (The extent to which this is due to neuropathology is an open question, but as a society we respect that and we value that.) Creative solutions are key in business: You can't really make a lot of money unless you open up a new market for yourself. And in science, too, we have to come up with creative experiments; it's not enough just to be good at statistics.

You can encourage creativity in a number of different ways. For starters, you can take people and engage in some mental play: Just combining ideas with no particular goal. We talk about this as brainstorming.

Two types of thinking are often involved in creative problem solving. Divergent thinking is coming at a problem from different angles, and exploring a variety of approaches, whether it's figuring out how to build the best children's toy or how to build a better submarine. Convergent thinking is kind of the opposite, where you prune down possibilities and kind of hone in on what the best solution might be by focusing on the goal and working through steps to accomplish it.

Here is an interesting point about creativity that I want to emphasize, as it's also counterintuitive. Imagine I said to one group, "Make me an awesome children's toy," and that I said to another group, "Make me an awesome children's toy; it has to have four wheels, and be powered by solar power, and it has to cost less than 20 dollars." Which group do you think would come up with a more creative toy?

What would be your first impression? Would you think that rules and guidance would improve creativity, that constraints would enable you to come up with something unique? It's true. Why might this be the case?

› Sample Answer

People have an idea about what a toy should be because of all the toys they’ve seen before. But when you impose guidelines, you have to cut some of these connections. You have to move away from functional fixedness, which opens up new possibilities.

« Previous