Inverse Problems...

... is a fancy way of saying "Study of Imaging." In the context of wave propagation, if you are given a source and some boundary conditions, you can work out the wave structure and evolution in pretty much every location in space-time. This is the "Forward Problem." Generally, forward problems are solvable (albeit often with difficulty). The inverse problem is posed as follows: if I am given some observations of a wave, say along one or several surfaces, can I infer the source? As you can imagine, this is not always possible. If the information given by the measurement is incomplete, the inverse problem is, in general, "ill-posed." This means that there might be several possible sources that would give rise to the same observation and we have no way to determine which one among them is the real one. (The terms ill-posed and incomplete are used in a loose sense here). Inverse problems is the field of study that tries to quantify when a problem is ill-posed and to what degree, and extract maximum information (again, in the loose, every-day sense of the word) under practical circumstances. For instance, an astronomer observing the sky with a telescope only might think that a blob of light originated from a single star; but if she applies an algorithm called CLEAN (or its variants), she might actually discern (the official term is "resolve") two or more stars in a constellation. This is the typical mode in which imaging system design benefits from knowledge of inverse problem theory. Note that this kind of imaging system is hybrid (telescope + computer). In addition to astronomy, these techniques benefit several application domains such as biomedical imaging and industrial inspection. The most spectacular success in the field of inverse problems was the invention of an inversion algorithm for Computed Tomography by Cormack (1963) and its experimental demonstration by Hounsfield (1973). The two shared the Nobel prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1979.

What do I gain by learning about inverse problems?

- Understand how the performance of imaging systems can be quantified; learn how to properly use terms such as "resolution," and "space-bandwidth product."

- Build intuition about the effects of noise on imaging, and how some of these can be survived.

- Learn about popular imaging techniques such Computed Tomography (CT) and functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) which rely heavily on the theory of inverse problems. See the example below.

- Share the instructor's fascination of blending inverse problems with information theory, through which information transfer from a physical object through an imaging system can be precisely quantified.

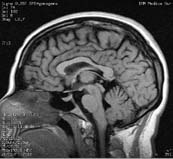

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) are two non-invasive imaging techniques that rely on data measured around a part of a subject's body (e.g. the head) to acquire information about what's going on inside the body part (e.g. the brain). The data are processed using a mathematical technique called Filtered Backprojection, which is a computationally efficient and stable way of computing the Inverse Radon transform. The MRI machine shown above is made by GE Medical Systems. An example of the kind of data that can be acquired via this technique is the image of a patient's brain shown below.

Image of patient's brain acquired via 'Filtered Backprojection' technique. (Image courtesy of Prof. Christof Koch. Used with permission.)