Experiments: 0 | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | X | XI | XII | XIII | XIV

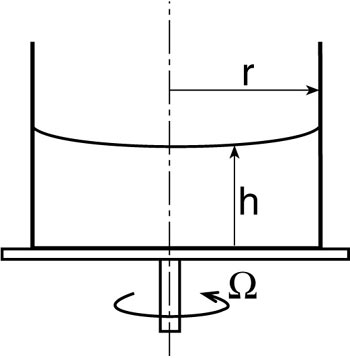

If our cylindrical tank is filled with water, set turning, and left until it comes into solid body rotation, then the free-surface of the water will not be flat - it will be depressed in the middle and rise up slightly to its highest point along the rim of the tank (see fig. below).

The shape of the free surface is given by

h(r) = h(0) + ((Ω²r²)/(2g)),

where h is the local depth, r is the distance from the axis or rotation, and h(0) is the depth at r = 0. Thus the free surface takes on a parabolic shape.

Let's put in some numbers for our tank. We can obtain rotation rates of up to 10 rpm (which is an Ω of 1 /s). The radius of the tank is 0.30 m and g = 9.81 m/s**2, giving

((Ω²r²)/(2g)) ~ 5mm,

a small fraction of the depth to which the tank is typically filled.

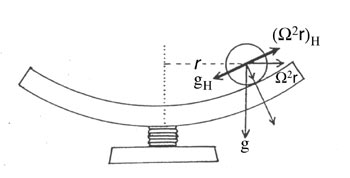

It is very instructive to make the surface of our turntable parabolic. This can readily be achieved by filling a large flat-bottomed pan with resin on a turntable and letting the resin harden while the turntable is left running (10 rpm works well) for several hours (see instructions). The resulting parabolic surface can then be polished to create a low friction surface.

Place a ball-bearing on the rotating parabolic surface - make sure that the table is rotating at the same speed as was used to create the parabola! Note that it does not fall in to the center, but instead finds a state of rest in which the component of gravitational force resolved along the parabolic surface is exactly balanced by the outward-directed horizontal component of the centrifugal force.