Courtesy of Dr. Romin Koebel. Used with permission.

Based on:

Cudahy, Brian. Change at Park Street Under: The Story of Boston’s Subways. Brattleboro, Vermont: The Stephen Greene Press, 1976.

Holleran, Michael. Bostons Changeful Times: Origins of Preservation and Planning in America. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Schaeffer, K. H., and Elliot Sclar. Access for All, Transportation and Urban Growth. Baltimore, Maryland: Penguin Books, 1975.

Milestones

Horse Car Lines

1850

In 1850, the Boston metropolitan area reached 2 miles from City Hall. For internal circulation, the city depended on walking and ferries. Boston and its adjacent communities were arranged to minimize walking. Horse car lines, became fixtures in American cities in the 1850s.

1852

Horse-drawn street railways starting in 1852 were a major force in restructuring the area. They attracted primarily passengers with bundles and parcels, or on special errands to a distant destination, (S&S p. 73). People started taking jobs in parts of the city too far to walk to.

Annexations

In the horsecar decades, Boston’s corporate limits achieved their greatest expansion through annexation.

- Roxbury on the mainland end of the Neck was annexed first (1868);

- Dorchester in 1870;

- Charlestown in 1874, and across the Back Bay the city annexed Brighton;

- West Roxbury was annexed last.

Brookline opted against annexation.

Horsecar lines were a force in reorganizing the spatially undifferentiated walking city into well-defined geographic neighborhoods for different ethnic and socio-economic groups, as the contrasting experiences of the Back Bay and the South End illustrate.

The South End never became an upper-class neighborhood as had been the intention, but rather turned into a rooming house area.

Development of the Back Bay began in the late 1860s by which time horsecars made distinct socio-economic neighborhoods possible. The Back Bay has preserved its character as upper-income residential area.

The horsecars were a success. High-density population led to a high-density ridership and the problems of commuter ridership and peaks had not yet appeared. Horse cars had limitations in speed and power.

Problems included: abuse of animals; feeding and stabling; public health issues. The electric street car was the logical successor (87).

Electric Street Car

1880

Frank Julian Sprague 1880 invented a flexible cable that transmitted electricity from an overhead wire to the streetcar’s electric engine. This invention eliminated the danger of an electrified third rail at ground level.

1887

The Massachusetts legislature enacted a bill bringing Boston’s West End Street Railway into existence.

1889

The first electric trolley cars appeared.

Streetcar companies, charging a flat 5 cents fare and offering free transfers, engaged in suburban real estate development. Since no one wanted to live more than a few minutes’ walk from the trolley stop, streetcar lines promoted suburbs of limited scope, and saw the electric street car as a means of developing outlying real estate. With this motivation, keeping fares down and extending lines as far as possible, was economically rational.

Through mergers Whitney put together a sizable system. By 1900, the outer limits of Boston’s electric railways reached some six miles from downtown. As cross-town lines were built, free transfer points were added (S&S p. 78). Downtown boomed from an influx of shoppers, the trolley, traveling at 10 to 15 miles an hour, brought from all over town.

1892

Street space was insufficient. Trolleys lined up bumper to bumper on Tremont Street. A State commission, charged with preparing a comprehensive analysis and making recommendations, called for measures to alleviate congestion, and for more efficient transit service. The report recommended a network of elevated railways and an underground tunnel.

Subway

1894

The General Court enacted a bill authorizing:

- a subway for electric trolley cars [The bill also authorized,

- the incorporation of the Boston Elevated Railway Company, and

- the formation of a public agency, the Boston Transit Commission].

The enabling legislation also stipulated that:

- the Boston Transit Commission provide for a bridge across the Charles with a transit line reservation, and

- East Boston both deserved and required transit service.

Alignment and geometry of the electric trolley car subway

The tunnel, two and two-thirds miles in length, was to approach the downtown from three directions by way of entry ramps called "inclines," which provided the interface between the tunnel and street levels.

- From the west, on Boylston Street at the Public Gardens.

- From the south at Tremont Street and Broadway. (Pleasant Street)

- From the north emerging a short distance north of Haymarket Square providing service to the North Union Station.

Three underground loops would enable trolleys to reverse directions.

1895

Ground was broken near the Public Gardens on Boylston Street opposite the Providence Railway depot.

The initial leg ran beneath Boston Common between the Park Street terminal and the Boylston-Public Gardens incline.

1896

The Boston Elevated Railway Company was designated to build and to operate a combination subway and elevated line under the provisions of a 20-year lease negotiated with the Transit Commission in 1896.

Park system.

1897

The first tunnel was not a product of the free enterprise system. The early history of the subway shows that real estate development was the driving force. Private entrepreneurs declined an offer to construct the first tunnel, because:

- it would involve considerable capital costs,

- run through the already built up downtown leaving no opportunity to offset these costs through capital gains from the abutting real estate.

Moreover,

3. the charter negotiated with the city required the system to maintain the five cents fare with free transfers for at least twenty-five years.

Entrepreneurs saw no profits in transportation. Consequently, the tunnel was built by the city.

- Tremont Street subway between the Park Street terminal and the Boylston-Public Gardens. The first leg of the Tremont Street subway between the Park Street terminal and the Boylston-Public Gardens incline opened. It removed 200 trolleys which had previously daily plied the street in each direction.

[Frank Sprague’s multiple-unit control was used for the first time on the South Side Elevated in Chicago].

1898

- The second subway leg between Park Street and the Haymarket incline opened.

The Main-Line El

Encouraged by the success of the Tremont Street/Boylston Street trolley tunnel, Boston moved ahead on the transit plans for Roxbury, East Boston, Charlestown and Cambridge (Cudahy, p. 17). The first of these involved the construction of a combination subway and elevated line that would bisect the downtown and connect intermodal terminals at Dudley Square in Roxbury to the south and Sullivan Square in Charlestown to the north. Trains of multiple-unit cars, using Frank Sprague’s multiple unit control, which had been used for the first time on the South Side Elevated in Chicago in 1897, would load and unload passengers at floor-level platforms. The system employed track- level third-rail current collection. These trains were put in service, while the tunnel beneath Washington Street bisecting downtown was being built. This meant running multiple-unit trains through the Tremont Street trolley subway until the Washington Street Tunnel was ready. Such routing necessitated 1) exclusion of the surface cars for a period of time, and 2) interim adaptation of the trolley subway tunnel to high platform usage.

Once the Boston Elevated Railway Company had built the tunnels for the city, the tunnels would be leased, to the Boston Elevated Company.

1901

Routing of El trains through the trolley subway commenced. A major change in surface car operations took place in conjunction with the opening of the Main-Line El between Dudley Square in Roxbury and Sullivan Square in Charlestown. Cars that had previously gone all the way downtown thus providing a "single-seat" ride between outlying areas and the central business district, their previous final destination, would now be rerouted into new intermodal terminals at Dudley Square in Roxbury and Sullivan Square in Charlestown (C. p. 20). At the Dudley terminal two sets of street car tracks ran up a pair of ramps to El platform level for easy transfer at grade. Each of set of tracks looped and returned to the street. In this manner several car lines could be accommodated on just two tracks.

- The loop track to the west of the El platform would be used by car lines reaching into the growing areas of Forest Hills, Jamaica plain and Roxbury Crossing.

- The loop track to the east would be used by a some half-dozen lines that fanned out into Roxbury and Dorchester" (p. 21). At Sullivan Square in Charlestown 10 stub-end trolley tracks - five on either side of the single elevated track - provided terminal facilities for the many feeder street car lines connecting with the El.

With 200,000 fares on the first day of operation, the Roxbury-Charlestown line was an immediate success.

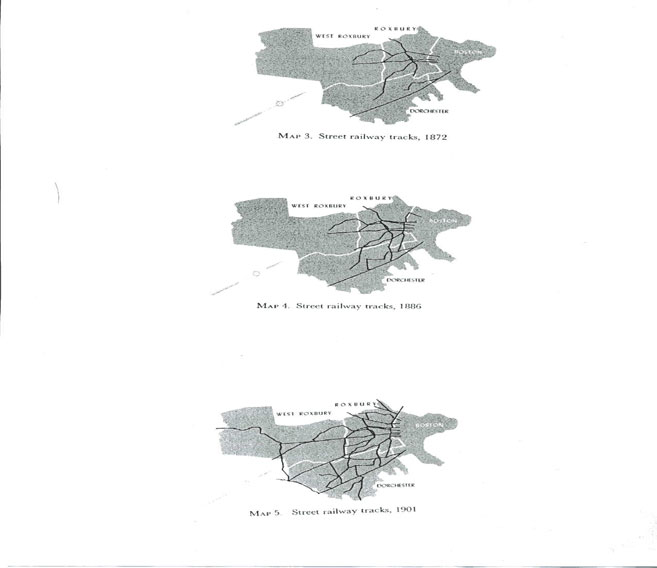

Street railway tracks.

Main Line El: Additions and Alterations

The Main Line El was underwent numerous additions and alterations. In August,1901 an all elevated right-of-way over Atlantic Avenue was put in service. Turning off the Main Line north of Dover street Station and rejoining the original route near North Station, it provided an alternate to the Tremont Street subway. The Atlantic Avenue service:

- linked the two major railroad stations and provided access to steamship berths and ferryboat slips. (C. p. 23).

- allowed an array of routing alternatives.

The routing alternatives included the following routings:

- from Sullivan to Dudley via Atlantic Avenue;

- an "Atlantic Avenue Circuit" train, in loop service through the subway and over the waterfront El;

- a North Station-South Station shuttle;

- from Sullivan to Sullivan;

- from Dudley to Dudley.

1904

The Tunnel beneath the harbor between East Boston and Downtown. In 1894 then first-term representative from East Boston John L. Bates had sought to have East Boston included in the legislation as both requiring and deserving of transit service. 10 years later, as Massachusetts governor, Bates presided over the opening ceremonies of the trolley tunnel under Boston Harbor. The tunnel connected Maverick Square in East Boston with Court Street in downtown. The geometric design of the route included sharp curves, steep gradients, close clearances. The route had been designed with no premonition of any subsequent conversion to multiple unit trains, which would take place in 1924, 20 years later.

With the opening of the below-harbor transit crossing, patronage of the municipally-operated ferry boats dropped off sharply. Only teams of horses and drays continued to use the old side-wheel steamers. The ultimate demise of the ferry boats contributed to the abandonment of the Boston Elevated Railway’s Atlantic Avenue Line. (Cudahy, p. 31). After the first harbor vehicular crossing, the Sumner Tunnel, linking East Boston to Boston for automobile travel, opened in 1934, the municipality-supported ferry closed. As a consequence, ridership on the Atlantic Avenue line, dropped so low that (S&S p. 89) the line was forced to close in 1938.

1906

Extension of the Tremont Street/Boylston Street electric trolley subway to Copley Square. For some years the shopping district had been extending to the west along Boylston Street in the direction of Copley Square. In 1906, the Boston Transit Commission noting that streetcar traffic on Boylston Street, had "practically reached its limit," recommended extending the Tremont Street/Boylston Street electric trolley subway at least as far as Copley Square, or further. The legislature, however, was to favor a route next to the river.

1907

Connecting to Cambridge

An additional bridge, the Longfellow Bridge, across the Charles River, was dedicated, but the built in transit way right-of-way would remain unused for five years. Local residents wanted five stations between Charles Street and Harvard Square. Opposing suburbanites on the other hand wanted through-express service, with a single station at Central Square where there were excellent transfer facilities to Brookline and Newton. (Cudahy, p. 41).

1908

Completion of the Main Line El/Tremont Street Subway Reverts to Previous All-Trolley Status. An important revision of the "Main Line El" occurred when trains were rerouted from the original Tremont Street subway into the new $8 million, 1.23-mile tunnel beneath Washington Street. With no provision for the running of surface cars in the new Washington Street subway, the Tremont Street subway reverted at once to its previous all-trolley status. The high platforms were torn out and the link-up ramp at Pleasant Street was reconnected. (p. 27). [The Pleasant Street ramp had been the interim transition between the elevated and underground parts of the Main Line El.]

1909

The Main Line El Extension to Forest Hills

The Main Line El was extended southward some 2 1/2 miles from Dudley to a new terminal at Forest Hills. The impressive new terminal was considered to be the "chef d’oeuvre" of rapid transit development in Boston up until this time.

1911

Extension of Tremont/Boylston Street Subway Tunnel to Copley Square

Boylston Street was experiencing increasing commercial development. Boylston business interests persuaded the legislature to approve an extension of the central trolley beyond the Public Gardens in an alignment that ran beneath Boylston Street. [The legislature had initially favored an alignment closer to the river].

1912

The Main Line El Extension to Lechmere Square in Cambridge

A 1.8 mile elevated route from the Haymarket incline to Lechmere Square in Cambridge was built. The elevated route served North Station.

1913

During excavations for the new Boylston subway at Arlington Street and again in 1939 during excavations for the New England Mutual Life Insurance Building, an important archeological discovery was made some thirty feet below street level - 65,000 sharpened wooden stakes - remnants of an ancient fish weir 2,000 to 3,600 years old. The weir extended into the northeastern section of the block bounded by Stuart Street and St. James Avenue.

1914

Westward extension of the Central Trolley Tunnel beyond Copley Square to Kenmore Square

A westward leg was spliced onto the original Tremont Street electric trolley Line. A two track tunnel under Boylston Street extended through Back Bay to a point east of Kenmore Square, where it connected to surface branches providing service to Brookline, Allston and Brighton. Merchants expressed concern about what good a subway with an uninterrupted run of four thousand feet from Copley Square to the existing downtown station at Tremont Street could do business interests on Boylston Streets between Clarendon and Tremont streets. Consequently, they pressed for an intermediate station at Arlington Street. The Boston Elevated Railroad Company, which held the transit franchise, opposed such a station. The state legislature also rejected an Arlington Street station.

1915

- Mayor Curley supported a renewed push for an Arlington Street station.

- The Arlington Street station bill and the district-revision bill were passed by the legislature together. (Massachusetts Special Acts and Resolves, 1915, Acts ch. 297 (Arlington Street station); 1915 Acts ch. 333 building heights). (H. 254).

- A "Center-entrance car" designed for service in the trolley subways was put in service, appearing first as motorless trailers.

1916

Extension of East Boston Tunnel to Bowdoin Square

The layout of the Court Street terminal of the East Boston tunnel was poor. Trolleys had "to change ends" before returning to East Boston. This situation was rectified by an extension across town (0.41 miles) to Bowdoin Station, allowing a loop turnaround, as well as an incline up and out to surface tracks in the middle of Cambridge Street. In this manner through trolley service between Chelsea and Cambridge could be provided." (C. p. 31)

1917

Extension Southward of Cambridge-Park Street Under Subway

The Cambridge-Park Street Under subway was extended incrementally toward South Boston to Broadway Station. By December a tunnel under the Fort Point Channel brought the line to Broadway Station in South Boston.

A fleet of center-entrance motor cars- was delivered. Initially assigned to East Boston Tunnel service, they were then reassigned to run outdoors in three-car multiple-unit trains on the Beacon Street and Commonwealth Avenue route, from which they dived into the original subway complex. The wide center doors were well-suited for the fast loading and unloading demanded at the Park and Boylston stations.

1918

Despite strong growth in ridership, in part due to the five cent fare and free transfers negotiated in 1896, the Boston Elevated was forced to declare bankruptcy. The State legislature had to step in passing the Public Control Act of 1918. The act assured transit service to the 14 cities and towns which the Boston Elevated had serviced.

But, in spite of reorganizations and a doubling of the fare, the transit system would never again be privately operated. Once the real estate holdings had been developed there was no incentive to operate a transit system that was not a money-maker. S&S p. 79

1919

Extensions of the Forest Hills - Charlestown line northward beyond Sullivan Square were discussed. Branches to destinations in Malden and Melrose, and Lynn were envisaged, but while trains did start running an additional elevated mile across the Mystic River, the new terminal at Everett remained temporary for over 50 years.

1923

A bill cleared the legislature enabling extension of the Cambridge Connector over the right-of-way of the Shawmut branch of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad to Worcester. (C. p. 46)

1924

Conversion of East Boston Line to Multiple Unit Trains. The East Boston Line had been built in 1904 for trolleys with no premonition of a conversion to multiple unit operation. Over an April double-holiday weekend, the East Boston Line underwent major change. Patrons went home aboard familiar trolley cars. They returned on Monday on brand-new steel multiple unit trains which they could board and leave at platform level. The grade in the tunnel was 5%, severe for trolleys, but even more so for multiple unit. subway trains. There were sharp curves and close clearances. Nearly four miles of third rail had to be hoisted onto pre-set insulators, electrically connected, and tested.

1927

Cambridge-Park Street Under Subway Extended beyond Broadway to Field’s Corner

The Cambridge-Park Street Under subway which had been extended incrementally toward South Boston beneath Fort Point Channel to Broadway Station in South Boston was further extended to the south to provide service to Fields Corner.

1932

The Central Trolley Tunnel is Extended West of Kenmore Square in Two Branches

The original Tremont Street-Boylston Street electric trolley subway was extended through and beyond Kenmore Square to inclines:

- at Blandford Street and Commonwealth Avenue, and

- at Beacon Street and St. Mary’s.

1933

The Huntington Avenue Branch of the Central Trolley Tunnel

The $8.5 million subway line Mayor James Michael Curley had proposed linking Copley Square and the Museum of Fine Arts opened. The line peeled off the Boylston Street subway west of Copley station, twisted under the Boston & Albany railroad yard and ran in a southwesterly direction beneath Huntington Avenue surfacing at an incline at Opera Place near Northeastern University. By eliminating surface cars from the Boylston Street corridor, the measure permitted abandonment of the incline at the Public Garden.

1934

The Sumner Tunnel

The Sumner Tunnel opened in 1934 linking East Boston to Boston for automobile travel. Ridership dropped so low on the municipality-supported ferry so that it was forced to close.

1937

The first President’s Conference Car (P.C.C.) car was delivered.

1938

Closing of the Atlantic Avenue EL

With the opening of the Sumner Tunnel and cessation of ferry service, ridership on the Atlantic Avenue EL, along the waterfront between North Station and South Station dropped so low that closing was the only rational solution. (S&S p. 89).

1940/1940s

- The Boston, Revere Beach & Lynn Railroad ceased operation.

- During World War II BE Railway reordered P.C.C.s in substantial numbers.

These were wired for multiple unit (m.u) train operation.

1941

A 20-car fleet of P.C.C.s. was delivered.

1945

The Legislature voted approval of service on the East Boston line northward beyond Maverick Station.

1950s

A still later order for 50 "picture window" P.C.C.s. 25 second-hand.

1952

East Boston Line Extended to Orient Heights

Service to Orient Heights

1954

East Boston Line Extended to Revere Beach

Service to Revere Beach. In the early fifties, the Blue Line (the East Boston Line) was extended past Logan International Airport to Revere. This expansion was less successful, than the subsequent Riverside Extension, because it competed with commuter trains and bus lines running directly from the major North Shore population centers and with automobiles able to reach Boston from the North over the newly opened Tobin Bridge and through the Sumner Tunnel.

1959

The Riverside Line

The most significant improvement to transit service occurred in 1959, when yet another extension of the Tremont-Boylston subway, was placed in service. The New York Central Railroad had sold to the MTA, a 9.4 mile grade-free right-of-way through Brookline and Newton. The "Riverside Line" was line was built on an abandoned railroad right-of-way which was free of street crossings at grade level. The first "transit tentacle" reaching out to Route 128, it connected downtown with Route 128 at an area just south of the region where the electronics industry had located and north of the warehouse region. Despite this mislocation, ridership more than justified it, as a carrier for traffic into central Boston rather than as a hauler of workers from the inner city to jobs on Route 128. "The forecasts had it that the bulk of patronage would come from the Brookline stations, but the more distant Newton stops drew so much the larger crowds that the Riverside storage yard quickly had to be enlarged to four times its original size." ["To free up the necessary P.C.C cars, buses were assigned to street car routes in Cambridge."]

1963

As part of Boston’s Government Center renewal project, the subway was slightly rerouted and the Adams Square stop was eliminated.

1964

- Extension of the Main Line EL, or Orange Line, to the Malden-Melrose border sharing the right-of-way of the Boston and Maine Railroad’s Reading Branch. Allows MBTA to dismantle elevated line from Haymarket to Everett. Replaced by an underwater passage of the Charles River.

- At the southern end of the Washington Street tunnel, the "South Cove by-pass" - a tunnel connector enabling Orange Line trains obviating the elevated route through Dudley and making it possible to reach Forest Hills, over a new right of way.

1971

- Yet the Central Trolley Tunnel continued to be overtaxed. Some relief occurred when the tunnel stopped accepting A - line trains with discontinuance of trolley service to Newton. Arborway cars no longer run into the tunnel.

- $ 124 million in new bonding authorization voted by the legislature specified $30 million for refurbishing.

1987

Back Bay Station. Dartmouth and Clarendon streets.

(Kallmann, McKinnell & Wood) Originally built in 1897, destroyed by fire in 1928, rebuilt in 1929, closed in 1979. Resurrected as a symbolic gateway to the city. 40 foot arches of laminated wood span entry to station and concourse between Dartmouth and Clarendon streets. Depression of the railroad below the water table using slurry wall technique. Financed by a federal grant for a public transit project in the Southwest Corridor. Arcades connected to Hancock Garage and an underpass to Copley Place. "Intermodal" transportation hub - interstate (Amtrak), intrastate (commuter lines), and local (subway) transportation - a stop on the new Orange Line relocated from Washington Street.

2000

Draft-Boston MPO Transportation Plan 2000-2025

PROJECTS INCLUDED IN THE 2002 NO-BUILD SCENARIO

These are projects that will come on line after January 1, 1996. They are either already completed, under construction or already advertised for construction.

North Station improvements:

This MBTA project includes the relocation of the above ground portion of the Green Line to Lechmere to underground. The new rapid transit station will include a super platform with easy transfers between the Green and Orange lines.

Blue Line platform lengthening and modernization:

The modernization program to allow for six car operation is underway. Modernization of stations from Wood Island to Wonderland is complete. Aquarium station will be renovated in conjunction with the Central Artery work.

South Boston Piers Transitway, Phase 1

This MBTA transitway will provide transit via tunnel from South Station (Boston) to the World Trade Center (in the vicinity of Viaduct Street) with an intermediate station stop at Courthouse Station (in the vicinity of Northern Avenue and Farnsworth). Construction on this project is underway and Phase 1 services is scheduled to begin in 2002. This does not not include Phase 2 - full build. Phase 2 connects South Station to Boylston Street Station. It also includes a surface route from the D Street portal to City Point. (South Boston).

PROJECTS ADDED AS THE 2025 BUILD SCENARIO

Silver Line - Washington Street, Section C: ($59,000,000). The Silver Line is to initially run along Washington Street from Dudley Square in Roxbury to Downtown Crossing in the city of Boston. The vehicles used on the route are 60-foot articulated compressed natural gas buses and their low-floor design makes them handicapped accessible. The buses operate in mixed traffic from Dudley Square to Melnea Cass Boulevard where they enter a reserved lane. At the Massachusetts Turnpike, the reserved lane ends and the vehicles enter mixed traffic again. Proposed stations for the Silver Line include Dudley Square, Melnea Cass Boulevard, Lenox Street, Newton Street, Cathedral Street, East Berkeley Street. Additionally, the vehicle will make stops at Herald Square, New England Medical Center, Chinatown, and Downtown Crossing. This Project is a Central Artery/Tunnel commitment. It is scheduled to be completed before 2002.

AITC (Airport Intermodal Transit Connector): ($35 million) This project would provide a new transit service in Boston from South Station Intermodal Center to the Logan Airport terminals. There would be approximately eight vehicles which would be similar to those used in the Silver Line-Transitway Section A, except that these vehicles have more luggage storage space. The service would use the MBTA South Boston Piers Transitway tunnel from South Station to South Boston and then the Ted Williams Tunnel to the five Logan Airport terminals. The capital portion of this service would be sponsored by MassPort. This service would provide for enhanced connection between the Red Line and Logan Airport. There would continue to be AITC bus service between the Blue Line Airport Station and the Logan airport terminals. This project must be completed by June 2004 as part of the administrative consent order between EOTC and EOEA relative to the Central Artery/Third Harbor Tunnel Project.

Green Line to Medford Hillside ($375,000,000); cost includes station construction and right of way improvements but not vehicles. The MBTA would extend Green Line trolley service to Medford Hillside. The extension begins at the relocated Lechmere Station in Cambridge, and continues along the Lowell commuter rail right of way through Somerville and Medford. The extension is 3.9 miles in length and there are four interim stations at Ball Square, Lowell Street, School Street, and Washington Street. 1994 ridership estimates were for 11,560 riders per day on the new extension, 3,660 of which were new transit users. The project is a SIP commitment. The extension to Medford Hillside is scheduled to be complete in 2011.

Red Line-Blue Line Connector. (Project cost to be determined). This project would consist of an extension of the MBTA’s Blue Line from Government Center/Bowdoin in Boston to the Charles Street Red Line station. The proposed Charles Street Station will not preclude a future Red-Line Blue Line connector. This connector was envisioned as providing a direct link between the only two transit lines that lack a direct station link in downtown Boston.

Silver Line - Transitway 2, Section B: ($713,000,000; cost includes construction of Transitway and new vehicles). The final phase of the MBTA’s Silver Line project, and the one which allows integration between it and the South Boston Piers Transitway, is the construction of a new tunnel through Chinatown and the Leather District in Boston. This tunnel would roughly follow the alignment of Essex Street and would connect the end of the existing Silver Line tunnel Boylston with Chinatown Station and South Station. This provides another connection with the Orange Line as well as direct connections with Red Line subway, Transitway, Commuter Rail, Amtrak and Intercity bus service. This phase of the Silver Line improves the level of service by utilizing the Green Line tunnel under Tremont Street with a portal at the Don Bosco High School building. The downtown end of the route would be adjusted to make stops at New England Medical and Boylston stations, allowing transfers to both the Orange and Green Lines. The Commonwealth has committed to apply for federal funding for this project by the end of 2004.

2002

South Boston Piers Transitway, Phase 1

Phase 1 services is scheduled to begin in 2002.

Silver Line- Washington Street, Section C. The section is scheduled to be completed before 2002.

2004

- The MBTA’s Super Platform project will link the Orange and Green Lines underground at North Statkion. The new connection will improve access from the North Station to the Back Bay.

- The Commonwealth has committed to apply for federal funding for Silver Line.

- Transitway 2, Section B: by the end of 2004.

- AITC (Airport Intermodal Transit Connector). This project must be completed by June 2004 as part of the administrative consent order between EOTC and EOEA.

2005

Silver Line South Boston Waterfront Service to begin operation.

2011

- Green Line extension to Medford Hillside;

- Silver Line - Transitway 2, Section B scheduled for completion.