Modules: 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.7

Introduction

Antibodies are useful tools in the lab. Today you will use antibodies to detect a protein on a blot. This technique, called Western analysis, can give you information about the size and concentration of the protein in the pool that was separated by SDS-PAGE. In your case today, you will use a Western to identify the expression of an M13 protein in infected cells and to determine if phage are present in the supernatant of infected cells. In general, detection depends on which antibody you choose, and the quality of your results depends largely on the quality of that antibody.

For Western analysis, a high quality antibody can have a relatively low affinity for its target protein. This is because the target is localized and concentrated on a blot, allowing the antibody to bind using both antibody "arms" thereby strengthening the association. Even an antibody that is loosely bound to the blot under these circumstances may dissociate then re-associate quickly since the local concentration of the target protein is high. The lower limit for protein detection is approximately 1 ng/lane, a value that varies with the size of the protein to be detected and the Western blotting apparatus that is used. For most acrylamide gels, the protein capacity for each lane is usually 100 to 200 ug (that would be 20 µl of a 5-10 ug/µl protein preparation). Thus 1 ng represents a protein that is approximately 0.001-0.002% of the total cellular protein (1 ng out of 100,000-200,000 ng). Obviously proteins that make up a more significant fraction of the total protein population will be easier to detect.

Many species can be used to raise antibodies. Most commonly mice, rabbits, and goats are immunized, but other animals like sheep, chickens, rats and even humans can be used. The protein used to raise an antibody is called the antigen and the portion of the antigen that is recognized by an antibody is called the epitope. Each antibody can recognize only a small portion of its antigen, typically 5 to 6 amino acids. Some antibodies are monoclonal, or more appropriately "monospecific," and recognize one epitope, while other antibodies, called polyclonal antibodies, are in fact antibody pools that recognize multiple epitopes. We will be using a monoclonal antibody against the p3 protein today, but for the sake of completion, the origin of both polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies are described.

Generating monoclonal antibodies.

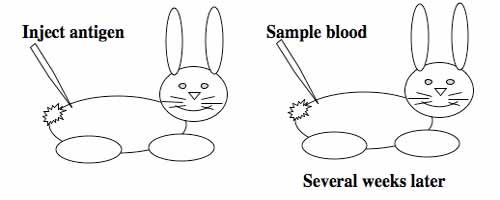

To raise polyclonal antibodies, the antigen of interest is first purified and then injected into an animal. To elicit and enhance the animal's immunogenic response, the antigen is often injected multiple times over several weeks in the presence of an immune-boosting compound called adjuvant. After some time, usually 4 to 8 weeks, samples of the animal's blood are collected and the cellular fraction is removed by centrifugation. What is left, called the serum, can then be tested in the lab for the presence of specific antibodies. Even the very best antisera have no more than 10% of their antibodies directed against a particular antigen. The quality of any antiserum is judged by its purity (that it has few other antibodies), its specificity (that it recognizes the antigen and not other spurious proteins) and its concentration (sometimes called its titer). Animals with strong responses to an antigen can be boosted with the antigen and then bled many times, so large volumes of antisera can be produced. However animals have limited life-spans and even the largest volumes of antiserum will eventually run out, requiring a new animal for immunization. The purity, specificity and titer of the new antiserum will likely differ from that of the first batch. High titer antisera against bacterial and viral proteins can be particularly precious since these antibodies are difficult to raise; most animals have seen these immunogens before and therefore don't mount a major immune response when immunized. Antibodies against toxic proteins are also challenging to produce if they make the animals sick.

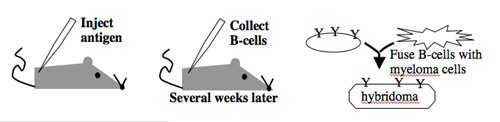

Antibody-secreting cells are first isolated from an immunized animal, usually a mouse, and then fused with an immortalized cell line such as a myeloma.

Monoclonal antibodies overcome many limitations of polyclonal pools in that they are specific to a particular epitope and can be produced in unlimited quantities. However, more time is required to establish these antibody-producing cells, called hybridomas, and it is a more expensive endeavor. Antibody-secreting cells are first isolated from an immunized animal, usually a mouse, and then fused with an immortalized cell line such as a myeloma. The fusion can be accomplished by incubating the cells with polyethylene glycol (antifreeze), which facilitates the joining of the plasma membranes of the two cell types. A fused cell with two nuclei can be resolved into a stable hybridoma after mitosis. The unfused antibody-secreting cells have a limited lifespan and so die out of the hybridoma population, but the myelomas must be removed with some selection against the unfused cells. Production of stable hybridomas is tedious and difficult but often worth the effort since monoclonal antibodies can recognize covalently-modified epitopes specifically. These are invaluable for experimentally distinguishing the phosphorylated or glycosylated forms of an antigen from the unmodified forms.

Making antibodies is big business since they can be useful therapeutics. The 2002 market for monoclonal therapeutic antibodies was estimated at almost $300 million and total therapeutic antibody market was estimated at more than $5 billion. These markets are expected to grow considerably, although successful antibody treatments may require clever engineering discoveries to "humanize" antibodies raised in other animals, as well as speedier development, well-protected patents, improvements in drug-delivery methods and cost efficient production of the therapeutics.

Protocols

Part 1: Probe Western Blot

- You should retrieve the blot that you made last time and pour the TBS-T + milk solution into a 50 ml conical tube.

- Wear gloves and cut the blot next to the markers in the middle of the blot.

- Place the blot lanes 1-4 in one blotting container, and the other portion of the blot (lanes 5-10) in another container.

- Add 15 ml of TBS-T + milk to each.

- Add 15 µl of anti-p3 antibody to the container.

- Cover the containers, label with your team color and the antibody they contain, and place on the platform shaker for 45 minutes. During this time, a representative from MIT's Environment, Health and Safety Office will speak with us about biosafety as it relates to cell culture work.

- Pour the antibody solution into a conical tube, writing the identity of the antibody and the date on the tube.

- Give the blots a quick rinse with TBS-T, enough to cover the blot (volume is not critical here).

- Wash the blot on the platform shaker 2 times with TBS-T at room temperature, five minutes per wash. Again the volume of the wash solution is not critical.

- Add secondary antibody (1:1000 Goat-antimouse-alkaline phosphatase) in 15 ml TBS-T and incubate on the platform shaker at room temperature for 30 minutes. During this time you can analyze your sequence data (see Part 2).

- Wash the blot as before (rinse and two washes).

- When you are done washing, mix 250 µl of each of the solutions from the alkaline phosphatase substrate kit into the provided tube of 25 ml 1X developing solution.

- Add developing solution and shake on the platform shaker watching for color to develop. Rinse the blot with water when bands are evident (you should anticipate what size protein you are looking for) but before the background of the blot becomes discolored. One of the teaching faculty will scan the blot and post the results for you.

Part 2: Sequence Analysis

Analysis of sequence data is no small task. "Sequence gazing" can swallow hours of time with little or no results. There are also many web-based programs to decipher patterns. The nucleotide or its translated protein can be examined in this way. Thanks to the genome sequence information that is now available, a new verb, "to BLAST," has been coined to describe the comparison of your own sequence to sequences from other organisms. BLAST is an acronym for Basic Local Alignment Search Tool, and can be accessed through the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) home page.

The data from the MIT Biopolymers Facility is available for you to examine, by logging in to the MIT Biopolymers Facility's dnaLIMS tool.

Rather than look through the sequence to magically find the relevant portion, you can align the data you just got with the standard M13KO7 sequence and the differences will be quickly identified. There are several web-based programs for aligning sequences and still more programs that can be purchased. The steps for using two web-based tools are sketched here. You do not have to perform your alignments using both programs (the results ought to be the same!!). They are both provided here for your reference.

Align with "CLUSTAL-W" from EMBL-EBI

- The alignment program is called CLUSTAL-W. It's default settings should work fine for this alignment and you do not have to enter your email address unless you want to.

- In the box labelled "Enter or Paste a set of Sequences in any supported format: you should type ">my_sequence_name," and on the following line paste the sequence text from your sequencing run.If there were ambiguous areas of your sequencing results, these will be listed as "N" rather than "A" "T" "G" or "C" and it's fine to include Ns in the query.

- On the following line you should type ">M13KO7" followed by the M13KO7 sequence from NEB's site for DNA Sequence Information.

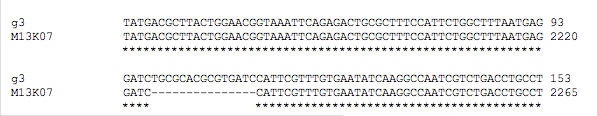

- Hit "run" and the sequence alignment will be available in several formats. If you scroll down the page there will be areas that are aligned. These are indicated with * as shown here.

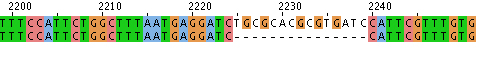

- Alternatively you can look at the data with "Jalview," scrolling to find alignments like this:

Align with "bl2seq" from NCBI

- The alignment program can be accessed through the NCBI BLAST page or from this link.

- To allow for gaps in the sequence alignment, uncheck the "filter" box. All the other default settings should be fine.

- Paste the sequence text from your sequencing run into the "Sequence 1" box. This will now be the "query." If there were ambiguous areas of your sequencing results, these will be listed as "N" rather than "A" "T" "G" or "C" and it's fine to include Ns in the query.

- Paste the M13KO7 sequence from NEB's site for DNA Sequence Information into the "Sequence 2" box. Numbers are OK to include.

- Align the sequences. Matches will be shown by lines between the aligned sequences. If you find a gap in the alignments look back at your sequence data for the missing bases.

You should print a screenshot of the relevant alignment, cross reference it against your oligo design and draw conclusions in your notebook. You might want to email yourself the alignment screen shot or post it to your wiki userpage.

Part 3: Analysis of Plaque Assay

Last time you titered the phage that had been secreted into the media while the infected cells were growing. Before you leave today be sure to count the number of plaques that arose on each plate and, if possible, calculate the PFU/ml associated with each sample. This will give you some idea if the modification to the phage genome has measurable consequences to phage production.

DONE!

For Next Time

- Your first draft of part 3 of your portfolio will be due when you arrive in lab next time. Email your draft to the instructors prior to arriving in lab.

- If you are planning to give an oral presentation next time, please be sure to email your finished Powerpoint presentation to Natalie or Agi. The order in which we receive your presentations will be the order of speakers.

- Prepare for the start of module 2 by browsing through the day 1 lab on siRNA Design and Startup in Cell Culture.

- Familiarize yourself with cell culture work by reading Guidelines for working in the tissue culture facility.

Reagents List

- TBS-T Tris-Buffered Saline + Tween

- monoclonal anti-p3 from NEB, raised in mouse cells

- polyclonal antimouse-AP from BioRad, raised in goat

- BioRad AP detection reagents

- 1 ml 25x detection stock + 24 ml H2O with 0.25 ml solnA and 0.25 ml solnB.