< Previous Week | Lecture and Studio Notes Index | Next Week>

Lecture 14: Parts and Registry

Lecture 15: Hypothesis-Driven Engineering

Lecture 14: Parts and Registry

Welcome Back Project Status Report

We'll start this session with a brief status report from each project team.

Challenge: Parts

Part 1: Poetic Parts

This challenge was inspired by the This American Life episode "Mistakes Were Made." Chicago Public Radio, April 10, 2009.

Consider the content of "This is Just to Say," a poem by William Carlos Williams.

The poem is often taught in poetry classes and often spoofed. Consider, for instance, the spoofs by Kenneth Koch in "Variations On A Theme By William Carlos Williams."

And one more spoof from the blog Somewhere in the Suburbs.

If you wanted to write your own spoof of the William Carlos Williams poem, you might begin by comparing the structure of these four poems. As a starting point they can be broken into 5 elements, namely

- 2 part situation

- "forgive me," and

- 2 part explanation.

or mapped into a table like so:

| SITUATION (PART 1) | SITUATION (PART 2) | FORGIVE ME | EXPLANATION (PART 1) | EXPLANATION (PART 2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Text of the afore-mentioned poems, as mapped into these elements, | ||||

Mix and Match Poetry

Now we can try to swap these poetic elements to see what interesting and clever spoofs we write. How about:

| SITUATION (PART 1) | SITUATION (PART 2) | FORGIVE ME | EXPLANATION (PART 1) | EXPLANATION (PART 2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox | and I broke your leg | Forgive me | but it was morning, and I had nothing to do | and I wanted you here in the wards where I am the doctor |

That seems to work but is it better? Let's try again:

| SITUATION (PART 1) | SITUATION (PART 2) | FORGIVE ME | EXPLANATION (PART 1) | EXPLANATION (PART 2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I chopped down the house | and which you were probably planning to air dry | Forgive me | they were delicious | it would not be so short and so small |

Well shoot, that's horrible. For one thing: It doesn't say anything understandable—this can be broadly described as a problem of functional compostion. For another thing: the connection between the different elements is, well, "awkward" at best—this can be broadly described as a problem of physical composition. If physical and functional composition of poems were working perfectly then every part would grammatically connect to the ones that flank it, and the meaning of the connected pieces would be interpretable at worst and clear at best.

Part 2: Genetic Parts

The physical and functional assembly of the poetic parts can be mapped to biological engineering once we define what a genetic "part" is. Let's start by extending what we did with the William Carlos Williams poem, namely let's consider a few natural genetic compositions, see what common elements compose them, and then try to bin these so we might compose new genetic elements by mixing and matching parts.

The bacterial lac operon is one we're already familiar with from our conversation earlier in the term.

Diagram of bacterial lac operon.

There are several genes encoded by this composition. LacI is made and we can see it's flanked by a promoter and a terminator. Lac Z, Y, and A are also made and they are flanked by a promoter + an operator on one end and a terminator on the other. So some genetic parts we might consider naming are:

- promoter

- operator

- protein-coding gene

- transcriptional terminator

Recombinant DNA technology gives us great power to move pieces of DNA around but it doesn't answer all the questions we might have about the resulting composition. For instance, are promoters/operators/genes and terminators all the parts we need to write a genetic program. Would the promoter that's in front of LacI make sense in front of LacZ, Y, and A? Is there something important about the junction of the parts?

For an introduction to systematic examination and nomenclature of genetic parts, watch Device Dude and Systems Sally's introduction in the BioBuilder animation "Genetic Programs: Why Parts Don’t Simply Snap Together."

Part 3: The Registry of Standard Biological Parts

The animation ends with a screen shot from the BioBricks™ Foundation, a not-for-profit organization that "encourages the development and responsible use of technologies based on BioBrick standard DNA parts that encode basic biological functions." BioBricks represent one kind of standard biological parts, standardized to enable reliable physical composition.

Just as we mixed and matched poetic elements, here are some mixed and matched genetic elements made from BioBrick parts.

Some mixed and matched genetic elements made from BioBrick parts. (Courtesy of the BioBricks Foundation.)

Just as we could identify "forgive me"-ish elements in the "this is just to say poems" we can see common elements in these genetic compositions: the green arrow element which is = a promoter, but which comes in different flavors (I13452, R0040 or R0011), the red stop signs = transcriptional terminators (B0010, B0012).

The part numbers as well as the DNA itself are collected at the Registry of Standard Biological Parts.

For your final project in this class, you will enter a part into the registry. We'll look at some good parts and some good documentation in class so you can model your work on those examples.

Before Tomorrow's Studio Time

If there are outstanding issues related to the system you're working on for your project be sure everyone on your team knows how you'll solve the issue(s) and make a plan to come to studio tomorrow with materials for finishing the system overview and getting good work done on the device list and the timing diagram.

Studio 8: Design Day #3

Part 1: Eau d'coli test/debug

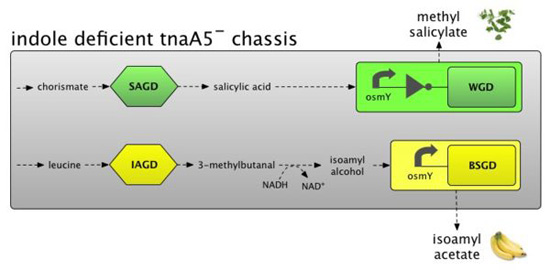

Eau d'coli device-level system diagram. (Courtesy of the 2006 MIT iGEM Team. Used with permission.)

Aye yay yay! Won't we ever get away from this Eau d'E coli project? Not yet! Take a close look at the device-level system diagram. You can't see all the underlying BioBrick parts (there are ~24 parts in total). If you were the designer of this system, do you think that the system would work if you just synthesized all the DNA as a single contiguous strand, transformed this new DNA into a cell, and let your genetic program rip!? Or, stated differently, what would be your next step if you tried to get everything working at once, and nothing happened, or, even worse, your engineered DNA killed the cell?

Having a plan for testing and debugging your projects is critical. To help you think about how to develop the best testing and debug plan for your 20.020 projects, spend the next 10 minutes working with your team to outline a testing and debug plan for the Eau d'coli system. Before you get started, designate one person on your team to act as spokesperson. Once the 10 minutes are up, we'll ask each spokesperson for an accurate description of your testing and debug plan. If you're having trouble knowing where to start, you might consider:

- Use the device level system diagram to sketch out a timing diagram (use a white board).

- Think about what this iGEM team could have done if they just added all this DNA to the cell, and then nothing happened (no smell, or worse, all the cells died). How would they go about figuring out what aspects of the project might be working, and what other components need to be revised or fixed?

- Finally, look again at the device-level system diagram. Is there anything about the system's design that makes testing and debugging easier or harder than it might be otherwise? Would you like to change any aspects of the system design to make testing and debug easier?

Part 2: Data-driven Decision-making

Consider once more the Melbourne 2007 iGEM project introduced during Week 1. In a series of questions at the end of their presentation video, the team gets asked about any changes to the gas vesicles device that might allow gas-filled cells to become even more buoyant. Their answer speaks to some scientific work others have done to understand the vesicle-encoding operon, research that has shown at least one gene in the operon is a negative regulator. By deleting that gene, the Melbourne team thinks they might make their cells even more buoyant. If you and your team were the Melbourne team, what would you do with this information?

First let's review one technical advance that opens a number of options for you, namely DNA synthesis. Then as a class we'll consider some options--weighing these (or others) in terms of their associated cost (both time and money).

- Use the entire gas vesicle operon to get the basic Coliform system working then tweak the system later to improve it.

- Wait to assemble your system until you can perform experiments to know more about each gene in the operon.

- Divide the team in half, with some launching into the project with the DNA as is, and others studying it and refining it.

- Spend one week in the library to read all you can about these vesicles and then decide.

- Place a DNA synthesis order for the full operon (6 kilobases) as well as every single gene knockout and double gene knockout.

Mapping These Ideas to your Project

Now it's time to look at the list of devices you have identified as part of your project (some of you may have a full list of needed devices and some of you will have only a partial list, in which case you'll have to consider these ideas now and then revisit them when your device list is complete). What might factor into the cost and time of assembling the devices into your working system? Do you know all you need to know about how they work? Are there easy ways to find out more? Do the devices already exist or will you have to make them yourself? You might want to make a chart that lists your degree of confidence in each device, where confidence is tempered by its cost/time/source/description and perhaps safety/security concerns...something we will return to next week.

Generate a list or table that might be useful as part of your Tech Spec Review next week.

Part 3: Project Work Time

Let's get busy working on the details of these projects!

Lecture 15: Hypothesis-Driven Engineering

"Faith is a poor substitute for reason"

Thomas Jefferson

As you hone in on the details of your projects, your team should plan ways to validate the system's operation and ways to learn from its glitches. We have two quick challenges for you today. The first illustrates that even the "best" answers you can offer that are consistent with all available data remain tentative, that the answer is either strengthened or revised by additional data and that all interpretations are subject to personal biases, human values and the various ways we all think about the world. The second challenge puts you midstream in a flawed design and requires that you consider the modes of failure to debug/troubleshoot the problem.

We will spend only 20 minutes on these challenges and then you and your team can use the rest of today's lecture time to prepare for next week's Tech Spec Review

Challenge 1: The Check's in the Mail

This challenge is adapted from Judy Loundagin's lesson for the Evolution and Nature of Science Institutes.

- One member of your team should serve as scribe (with notebook sheet to be provided). Another should be spokesperson (see item 7, below).

- Each team should get one envelope that is filled with fictional checks. Do not look at the checks yet. All envelopes have the same checks.

- Remove and examine 4 checks only.

- Discuss a plausible scenario which involves those checks.

- Once your group has agreed on a reasonable scenario that accounts for the checks, and the scribe has written it down, then you can draw 4 more checks from the envelope. As tempting as they are, the unchosen checks must stay in the envelope, unexamined.

- Reconsider your initial scenario to include the information you can glean from all 8 of the checks.

- We will take 1 minute to hear from each team. The spokesperson should detail

- the content of the first 4 checks,

- the way your team considered their content and

- the initial conclusion you drew

- the details of the next 4 checks and

- the revisions you made to the scenario to accommodate the information.

Finally, the spokesperson should say what kind of check they would expect to see in the envelope if their scenario is correct or what kind of check would blow their ideas out of the water and demand a full re-write of their explanation.

Challenge 2: Soap Stress

Stresses on a cube: compressional stress (left), tensional stress (center), shear stress (right). (Images courtesy of NASA JPL.)

This challenge is adapted from one described at teachengineering.org. We will skip the preliminary descriptions of plate tectonics and just remind you of three stresses that give rise to deformation: compression, tension and shearing forces.

Soap stress in action.

- Begin by looking at how the packaged soap is breaking during shipment from the factory to the distributor (a sample of the broken soap will be available for you to look at). Decide as a team which kind of stress could be leading to this kind of damage. Pick only one kind (i.e. not a combination of tension and shear) and rate your confidence in that choice on a scale of 1-10 (1 = we had to pick something so we picked this, 10 = I'd bet my house on it)

- Now start counting costs to analyze and fix what you believe to be the failure mode.

- if you'd like to stress an unbroken soap bar, each bar costs $1

- if you'd like to use paper to wrap each bar of soap, each sheet of paper costs $0.01

- if you'd like to use a small piece of cardboard to line each bar of soap, each piece of cardboard costs $0.05

- if you'd like to use larger sheets of cardboard to line each 12 pack of soap, each large sheet costs $0.50

In 5 minutes, your team will be asked

- which of the three stresses you believe could be breaking the bars of soap

- how confident you are with that choice

- what you'd propose as the best way to fix the problem

- how much you spent to arrive at that recommendation and what your proposed solution will cost

- and finally if you are more or less confident in the source of stress that's breaking the soapbars after this quick round of failure analysis, and debugging.

Be sure to wash your hands before you touch your eyes if you've been breaking soap to test it.

Mapping These Challenges to your Project

There is no such thing as either complete knowledge or flawless design. And if you believe, as Henry Petroski does, that "...the central goal of engineering is still to obviate failure, and thus it is critical to identify exactly how a structure may fail,"1 then you and your team will dedicate effort

- to collecting relevant data that validates or disproves the ideas in your own project; and

- to anticipating failure modes so debugging your design is trivial rather than backbreaking.

These ideas of validation and debugging should be included in your Tech Spec Review, at least a first go at them.

1 Petroski, Henry. To Engineer Is Human: The Role of Failure in Successful Design. New York, NY: Vintage, 1992, p. 195. ISBN: 9780679734161.

Petroski, Henry. To Engineer Is Human: The Role of Failure in Successful Design. New York, NY: Vintage, 1992, p. 195. ISBN: 9780679734161.

< Previous Week | Lecture and Studio Notes Index | Next Week>